There are a lot of digestible explainers out there for popular ZK proof systems and their components, but reading the actual papers is hard; because the authors write rigorous proofs that the system has various security properties. While trying to understand proof systems that aren’t as “popular” as the classics like PLONK and STARKs, I became unsatisfied with not easily knowing why the protocol works, and found it helpful to look into these security proofs to make sense of them.

For this blog post, we’ll be focusing on Bootle16, an important paper in the same lineage of Bulletproofs and Halo.

Bootle16 starts by giving 12 numbered definitions, placed into different categories. In this blog post, I’ll focus on two specific definitions from the Zero-Knowledge Arguments of Knowledge section,

- Statistical Witness-Extended Emulation

- Name sounds complicated, but is quite easy to understand.

- Special Honest Verifier Zero-Knowledge

- A bit more complicated, took me quite some time to demystify.

If you are inventing a new zkSNARK scheme, you have to formally prove that your scheme has these properties (or often substituting with similar properties) in order to have what’s needed for the “zk” and “ARK” parts of zkSNARK. The “S” comes from succintness (concretely efficient), and the “N” comes from being non-interactive, which comes from the well-known Fiat-Shamir heuristic in most cases.

Statistical Witness-Extended Emulation

This property is related to something called knowledge soundness. This specific property is about ensuring (with a high probability), that the prover truly knows a witness that satisfies the statement, and didn’t just make up some crap to pass the checks. It’s not the only security property that needs a formal proof; other properties such as completeness are also needed to trust these constructions.

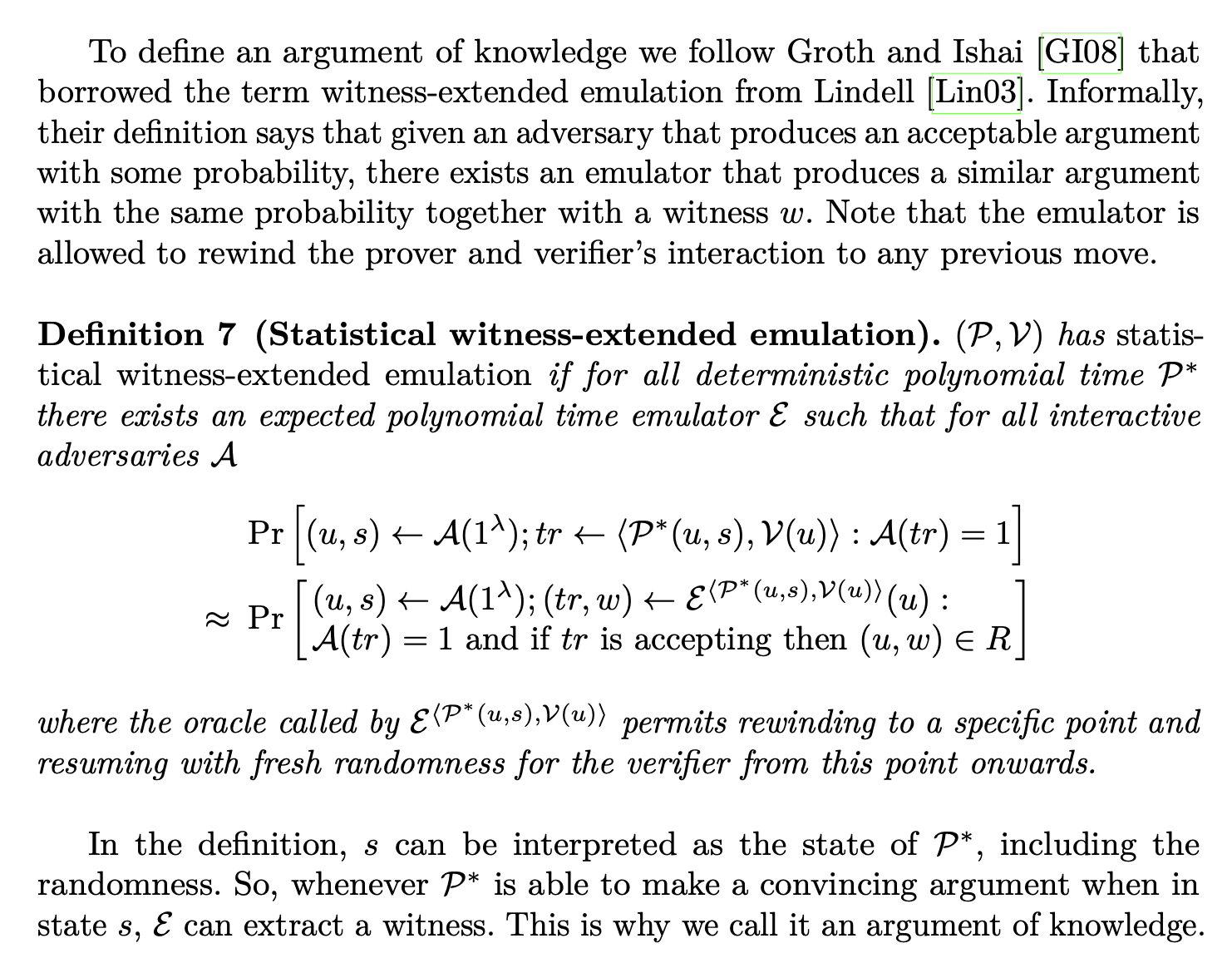

In the paper, we see the Statistical Witness-Extended Emulation introduced (with a lot of scary jargon and notation) here:

To put it in more simple terms, it means the probability that some algorithm can brute-force a satisfying witness for the statement is equal to the probability that some algorithm can brute-force a junk input that passes all the proof system’s checks.

That means if you’re a verifier and you receive a valid proof, even if the prover brute-forced proof-generation with a supercomputer, it’s just as likely that they brute-forced a valid input to the circuit than that they brute-forced some junk.

So, if it’s, for example, a zkEVM with statistical witness-extended emultation, then the attacker may have accidentally generated a valid Ethereum block while trying to brute-force a validity proof ^_^

Special Honest Verifier Zero-Knowledge

While statistical witness extended emulation is related to the “ARK” (argument of knowledge) part of our zkSNARK, this property Special Honest Verifier Zero-Knowledge is related to the ZK part; ZK being a popular buzzword that is rightfully associated with privacy. To dumb it down to an offensive degree- this is how we know our construction is… private.

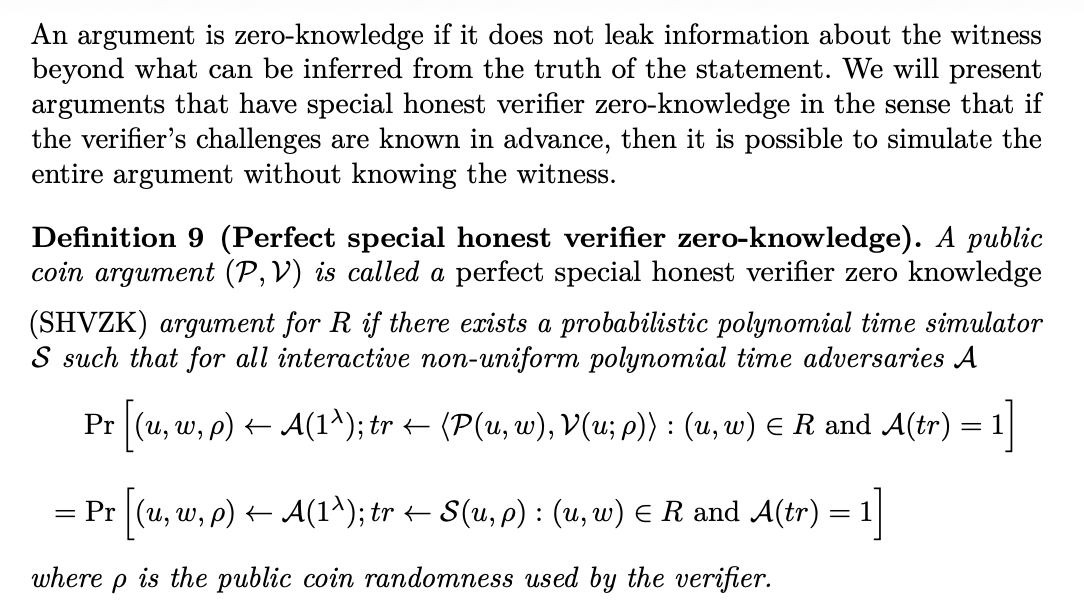

From the paper, we see:

Notice how they present an equation with the form

$$Pr[...] = Pr[...]$$. The property is achieved for our scheme if these two probabilities are equal. Notice how the two sides have these different terms:

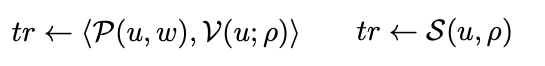

and both start out with $(u,w,p) \leftarrow A(1^{\lambda})$. To understand the difference, recall from proof systems that you may be familiar with that proof consist of transcripts of messages, sent between a prover and verifier. These two terms describe different ways that these transcripts might hypothetically be generated.

The difference between $\langle P(w, u) , V(u) \rangle$ and $S(u, p)$ is that the former is a normal interaction between a prover and verifier (resulting in a transcript), and the latter is an algorithm called a simulator (also resulting in a transcript).

To understand the simulator, recall that our zkSNARK has zero-knowledge (is concretely private), if the proofs it produces don’t leak anytihng about the secret witness (private inputs) that were used to create it. Imagine we are a scientist in a lab trying to break our own proof system in a specific way that will help us know if the proofs leak info about the witness. First, we will generate some real witness + instance pairs that satisfy the relation (valid inputs to the circuit for some statement). We will also pre-generate some randomness, instead of what an honest verifier would normally do, which is provide truly random challenges in response to the prover’s messages during their interaction (or after being fiat-shamir’d, it would normally derive randomness with hashes from the messages).

We can get away with doing this because we are a scientist in a lab, and not using a production implementation of the proof system.

Then, note that the simulator $S(u, p)$ does not take the witness as inputs, in contrast to the real prover / verifier pair. The simulator exploits the fact that the randomness is pre-generated to cheat at the protocol and produce seemingly-valid transcripts without knowing the witness.

The last piece of notation is this:

$A(tr)$ is a function that tries to determine if a transcript $tr$ came from a real prover-verifier interaction, we can call it the distinguisher, and it returns “1” if it thinks a transcript came from a real prover-verifier, and “0” if it thinks it came from a simulator.

Putting it all back together, the equation basically says “the probability that our distinguisher will return 1 on a real transcript is equal to the probability that it will return 1 on a transcript from the simulator”.